Is Your Pre-Litigation Mediation Clause Well-Drafted? A Cautionary Tale from California

September 9, 20195 Ways Mediators Can Add Value to Hospital Communication and Resolution Programs

September 18, 2019Insurer That Relied On Flawed Decision Tree Analysis Hit With $7.2M Judgment For Rejecting Settlement Offers After Failed Mediation

The dynamic present in personal injury mediations is fairly straightforward. The defendant’s insurer (or the defendant, if self-insured) will estimate the risk of a jury verdict for the plaintiff on liability, and discount the likely damages by that risk to determine a reasonable settlement range. On the other side of the table, the plaintiff’s attorney will try to raise the settlement range by persuading the insurer that the risk of liability, and/or the magnitude of the potential damages, are materially higher than the insurer has projected.

The dynamic present in personal injury mediations is fairly straightforward. The defendant’s insurer (or the defendant, if self-insured) will estimate the risk of a jury verdict for the plaintiff on liability, and discount the likely damages by that risk to determine a reasonable settlement range. On the other side of the table, the plaintiff’s attorney will try to raise the settlement range by persuading the insurer that the risk of liability, and/or the magnitude of the potential damages, are materially higher than the insurer has projected.

Among the uncertain factors both sides must weigh in their case evaluations are the degree of the plaintiff’s contribution, if any, to the accident that led to injury or death; the level of sympathy a jury will have for the plaintiff (or for the plaintiff’s survivors if there was a fatality); and the reputation of the judge for being either pro-plaintiff or pro-defense (if there are contested legal issues that may be a close call).

A recent Texas federal court decision offers a fascinating inside look at how this dynamic played out in a bicycle fatality case, including extensive, but flawed reliance on decision tree analysis. See American Guarantee & Liability Ins. Co. v. ACE American Ins. Co., 2019 WL 4316531 (S.D. Tex. Sept. 11, 2019).

The Claim

The case concerns a claim by an excess insurer (AGLIC) that the primary insurer (ACE) breached its Stowers duty to accept a $2 million settlement offer within the limits of its coverage. For those readers unfamiliar with Texas law, the Stowers duty obligates insurers to accept reasonable settlement demands within policy limits (as evaluated under a reasonably prudent insurer standard).

As a result of ACE’s breach of that duty, a jury returned a verdict of nearly $40 million in a wrongful death case, which AGLIC ultimately settled for $9,750,000, resulting in a payout of $7,750,000 from its secondary layer.

The Facts

The accident at the heart of the case was tragic. Mark Braswell (“Braswell”) was bicycling when he hit the back of a parked landscaping truck owned by the Brickman Group (“Brickman”), and suffered fatal head injuries. Braswell was survived by his mother, his wife of twenty years, and two children — a 13-year old son, and a 9-year old daughter. Braswell’s survivors sued Brickman, and the driver of the truck, Guillermo Bermea (“Bermea”).

Brickman’s insurance coverage included a $500,000 deductible/self-insured retention (which was included within primary coverage limits), a $2 million primary business auto policy issued by ACE, a $10 million excess policy issued by AGLIC (to immediately follow the ACE policy), and a $40 million excess policy issued by Great American Insurance Company (which was not a party in the case because its layer was not ultimately triggered).

After the lawsuit was filed, Brickman tendered the deductible, and ACE took over the defense of the case and settlement negotiations.

The claims adjuster asked the attorney assigned to defend the case (a lawyer named Leibowitz) to prepare a pre-trial report to help the carriers evaluate the claim and prepare for mediation. The report concluded that defendants had a “very strong liability case” on the theory that Braswell was responsible for the accident because he was not paying attention when he was cycling. In support of this conclusion, the report cited compelling evidence that Braswell’s head was down (i.e., he was not looking ahead) when he struck the truck.

Still, there were also weaknesses in the defense case. First, the driver (Bermea) testified that although it was legal to have parked where he did, he believed it was dangerous to do so. Further, Bermea’s testimony concerning how long he had been parked was inconsistent, leading plaintiff’s counsel to argue that Bermea had stopped short, and left Braswell no time to react. Supporting plaintiff’s theory was the absence of cones around the truck at the time of the accident (which suggested that Bermea had just stopped; otherwise, he would have put out cones).

Separately, there was the sympathy factor. Braswell and his wife were firefighters, and Braswell had been cited for bravery for rescuing a double amputee from a burning building. Additionally, after Braswell’s death, his daughter began cutting herself, attempted to overdose, and spent a week in a mental hospital. She also frequently left notes for her father at the scene of the accident.

Finally, in defense counsel’s experience, the trial judge designated to hear the case “tended to favor the plaintiff side,” which meant that “close rulings” would likely go against the defendants. Defense counsel also held plaintiff’s counsel in high regard, and expected him to do an excellent job at trial.

Decision Tree Analysis

At this point, I’ll interject with a brief overview of decision tree analysis, which is a method of valuing lawsuits for purposes of deciding whether to settle or litigate. As we’ll see below, it appears defense counsel used some form of decision tree analysis to value Braswell’s case for purposes of mediation and settlement, but did not employ the technique correctly.

At bottom, assigning a value to a lawsuit represents decisionmaking under conditions of uncertainty. For example, there is uncertainty concerning the admissible evidence that will be available at trial to support a client’s positions, how a judge will rule on key motions (e.g., dismissal, summary judgment, evidentiary), how a jury will react to the evidence and the witnesses, and the measure of damages if liability is found.

The difficulty in valuing cases is exacerbated by the imprecise language that litigators often use to describe these uncertainties. For example, in the current case, defense counsel advised that the defendants had a “very strong” liability case, from which we can surmise that he believed it was “very likely” that a jury would either find that the defendants were not negligent, or that (even if defendants were negligent) Braswell caused the accident by biking with his head down.

Yet, defense counsel also conceded it was “possible” a jury might conclude that Braswell was not responsible for the accident because there was some evidence to suggest the truck driver stopped short. It was also acknowledged that sympathy for the plaintiffs “might possibly” affect the jury’s deliberations. Finally, defense counsel also recognized that the trial judge was pro-plaintiff, which meant there was a “good chance” he would rule in favor of the plaintiffs on any close calls.

It should be clear that phrases like “very strong,” “very likely,” “possible,” “might,” and “good chance” are highly imprecise, and will mean different things to different people. For example, does “very strong” mean a 90% likelihood of prevailing, or an 80% likelihood of prevailing? The lawyer who provides the assessment might be thinking “80%” while the client interprets “very strong” as “90%,” which means the client perceives the litigation as meaningfully less risky than the lawyer intends to convey.

To ensure that counsel and client are on the same page concerning the likely outcome of a case, a method is needed to convert imprecise qualitative assessments into unambiguous quantitative probabilities that can be mathematically combined to yield an expected value for the case to appropriately guide decisionmaking about settlement.

Decision tree analysis is such a method. The technique:

- breaks down a case into key binary uncertainties (e.g., will a jury find the defendant was negligent or not, will the judge admit this evidence or not);

- assigns probabilities to the alternative outcomes for each uncertainty (e.g., 75% chance of finding negligent, 25% chance of finding not negligent);

- combines the multiple probabilities using a “tree” format (using the multiplication rule of statistics described below), and

- applies those probabilities to potential damage awards in a weighted fashion to calculate an expected value for the case.

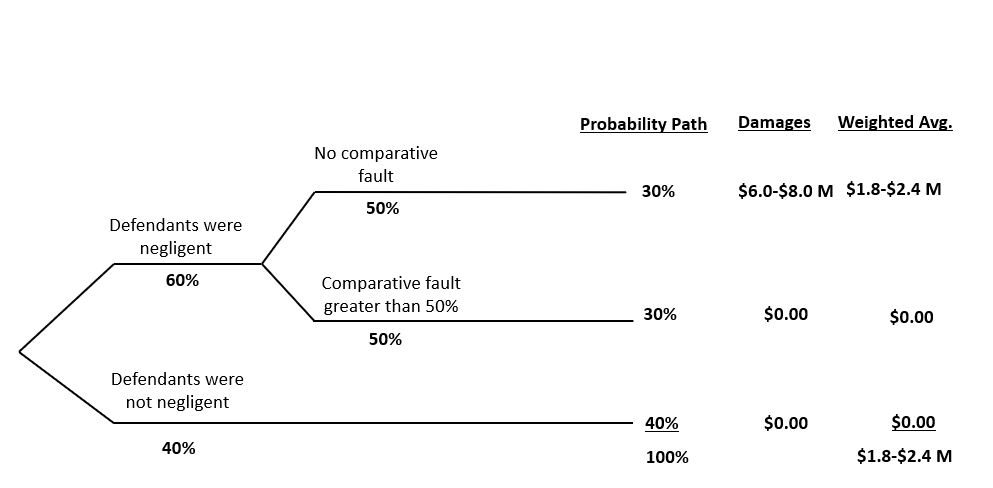

That’s certainly a mouthful. But let’s consider an example. In the case under discussion, we might say there is a 40% chance that a jury will find that the driver was not negligent when he stopped the truck on the road (how we get 40% is discussed further below; for now we’ll focus on the math).

Moreover, even if a jury were to find the driver was negligent (60% chance), and it proceeds to the question of comparative fault, there is a 50% chance that the jury will find that Braswell was more than 50% responsible for the accident (which would bar recovery under Texas state law).

Using decision tree analysis, we can combine those probabilities as follows: as noted, a 40% chance of “not negligent” necessarily means a 60% chance of “negligent.” But even if there’s a 60% chance a jury will find the defendants were negligent, there’s still a 50% chance in that scenario of completely barring recovery based on Braswell’s comparative fault, which means we need to multiply the 60% by 50% (under the multiplication rule of statistics, which states that the probability that A (“negligence”) and B (“more than 50% responsibility”) both occur is equal to the probability that A occurs times the conditional probability that B occurs given that A occurs). That calculation yields a 30% chance of barring recovery based on comparative fault (even if the defendants are found negligent).

The 40% we generated above, plus the 30%, equals 70%, which means there’s a 70% chance of a defense verdict either because a jury finds the defendants were not negligent, or (negligence notwithstanding) finds that Braswell was more than 50% at fault.

Finally, for the sake of simplicity, let’s assume that the remaining 30% balance of what might happen at trial translates into a full recovery for the plaintiff (in fact, that recovery would likely be adjusted downward depending how the jury apportions fault, assuming that Braswell was less than 50% responsible for the accident, but more than 0% responsible).

With our percentages in hand, let’s look at damages. If the potential jury verdict (assuming liability) is in the range of $6-$8 million (both economic and non-economic damages), we would multiply that range by the 30% probability of a plaintiff verdict, which means an expected value for the case of $1.8 million to $2.4 million (i.e., 30% x $6-$8 million).

Here’s a very simple “decision tree” graphic illustrating the calculations above:

Just to be clear, this analysis is not a prediction about how the case will come out if tried. Instead, it is a weighted probability assessment stating that if this case was tried ten times (or a hundred times) before a jury in this particular county before this particular judge, 7 out of 10 of those trials should result in a defense verdict.

It’s like flipping a coin. I know the odds of heads is 50/50, but I certainly cannot predict whether an individual flip will be heads or tails. But if I flip the coin one hundred times, it’s likely the coin will land on heads around 50 times, and on tails around 50 times.

Avoiding Garbage-In, Garbage Out

A crucial question, of course, is how one arrives at the percentages used above. We can’t just pick percentages out of thin air because “garbage in” results in “garbage out,” and the expected value we calculated would be meaningless for purposes of decisionmaking.

Instead, as decision tree analysis pioneer Marc Victor explains*, we need to develop a list of reasons why each of the alternative outcomes for each binary uncertainty is more or less likely. For example, the reasons why a jury might find the defendants were “not negligent” in the case at hand is that the truck was parked legally, and the weight of the evidence suggests that Bermea did not stop short.

On the other hand, the jury might find that defendants were negligent because Bermea conceded it was still “dangerous” to park where he did (even if legal), and there is some evidence that Bermea might have stopped short. And perhaps Bermea won’t come across as a credible witness, given his inability to remember key details about the accident. And of course, there’s the sympathy factor, and the skilled plaintiff’s counsel.

Weighing all of those considerations, a reasonable trial attorney might conclude there is a 40% chance of a jury finding not negligent, and a 60% chance of a jury finding negligence. The trial attorney would then similarly develop a list of reasons for why (or why not) a jury would find that Braswell was more than 50% responsible for the accident.

Updating a Decision Tree Analysis as a Case Progresses

Victor stresses that the probabilities used in a decision tree are not static numbers, but must constantly be updated as a case progresses, and more information concerning the likely resolution of various uncertainties becomes available.

For example, defendants can try the case before a mock jury, and solicit their feedback on the evidence and testimony they found most compelling. As discussed below, defense counsel used a mock jury for that purpose in this case, but seemingly failed to update the percentages in their decision tree analysis to account for the feedback received from the mock jurors.

Back to the Case: Defense Counsel’s Decision Tree Analysis

With that background, it’s clear from the court’s decision that ACE’s defense counsel performed a decision tree analysis of some sort when evaluating the case:

Leibowitz prepared a Case Summary and Evaluation on August 10, 2016 (the “August Memo”). In the August Memo, Leibowitz estimated the range of a potential verdict to be between $6,000,000 and $8,000,000. He said that the plaintiffs’ expert put economic damages between $2.85 million and $3.365 million, which was “certainly reasonable.” He stated:

Based upon all the foregoing, we believe this is a defensible case on behalf of Brickman. We believe that it is likely that the jury will find that Defendants were not negligent. However, even if a jury were to find that Defendants were negligent, we believe that a jury would find a significant amount of contributory negligence on the part of Mr. Braswell with a very good chance of Plaintiff’s negligence exceeding 50%. As you know, if a jury were to determine that Plaintiff’s contributory negligence exceeded 50% he would be barred from any recovery. At this time, we believe that if we tried this case 10 times that we would get a finding of no negligence on behalf of Defendants or a verdict where Plaintiff’s negligence exceeds 50%, 7 out of 10 times. If Plaintiff’s negligence does not exceed 50%, we believe that in most cases a jury would find Plaintiff’s negligence to be in the range of 30-50%.

Leibowitz concluded that the case had a settlement value in the range of $1.25-$2 million. (emphasis added).

Three comments:

First, Liebowitz assigned a settlement value in the range of $1.25-$2 million. However, as noted above, if Liebowitz assessed a 70% chance of a defense verdict, and total economic and non-economic damages were $6-$8 million, then the expected value of the case would be $1.8-$2.4 million (substantially higher than the range identified by Liebowitz).

The source of this discrepancy is not clear. It appears that Liebowitz might have been proposing a “low ball” settlement range below the expected value of the case. Alternatively, he may simply have made an ad hoc adjustment to the expected value based on intuition without disclosing what factors drove that modification.

In either case, he should have better explained his thinking since the $1.25-$2 million range specified became the de facto standard by which ACE subsequently evaluated all of plaintiff’s settlement offers even though (i) this range was well below the expected value of the case according to Liebowitz’s own initial assessment of the likelihood of a defense verdict (70%), and magnitude of the potential damages ($6-$8 million), and (ii) subsequent developments in the case dramatically increased the likelihood of a plaintiff verdict and rendered this settlement range even more out of line with expected value.

Second, readers will notice that Liebowitz used qualitative assessments such as “likely” and “very good chance.” But he concludes with a quantitative assessment — a 70% chance of a defense verdict. So the question is, how did he get from “A” (qualitative assessments”) to “B” (quantitative prediction)? The court’s recital of the facts indicates that defense counsel was aware of the weaknesses in the case. But it’s not clear how those weaknesses were incorporated into the analysis. Again, unhelpful because (as will be shown) as the case progressed and new information became available, there was no mechanism to easily update the case’s expected value by adjusting relevant percentages.

Third, readers of our analysis above will note that we tried to arrange the probabilities to reach the same 70% probability of a defense verdict that Liebowitz calculated. But to do that, we had to assign only a 40% chance of a jury finding not negligent. We could have instead assigned a 60% chance of “not negligent,” and then a 25% chance of finding that Braswell was more than 50% responsible for the accident (40% (negligent) x 25% (more than 50% responsible) = 10%).

But Liebowitz indicated it was “likely” a jury would find that the defendants were “not negligent” and there was a “very good chance of Plaintiff’s negligence exceeding 50%.” In this author’s mind “likely” and “very good chance” both mean meaningfully greater than 50%. But there is no way mathematically to arrive at a total probability of 70% for a defense verdict where the likelihood of “no negligence” and “comparative fault exceeding 50%” are both greater than 50%. So, again, it’s not clear how Liebowitz arrived at his 70% quantitative prediction based on the qualitative assessments that he shared.

ACE’s Internal Valuation

More mystifying was how ACE’s internal team valued the case. Here is how the Court described their analysis:

Adamo and Albin calculated the settlement value at $600,000. Adamo testified that he reached this number by multiplying ACE’s policy limit of $2 million by 30%, Leibowitz’s estimate of the likelihood of a plaintiff verdict. Albin agreed with this analysis. (Tr. 60-61; Albin Depo). Smith, on the other hand, agreed that the settlement value reached by ACE was $600,000, but disagreed that they reached that value by calculating 30% of the $2 million policy limit. He said that they reached the value by “looking at ground up what the value of the case was.” (Tr. 576-577; Smith Live). However, the ACE claim log clearly states that ACE believes that “we have an approximately 70% chance of a defense verdict . . . Therefore, we are reserving at 30% of our limits and will attempt to settle with plaintiff up to that amount.

The obvious error here is that ACE’s internal team multiplied their policy limit by 30%. But the policy limit represents ACE’s exposure, not the potential damages. As noted, under a decision tree analysis, the correct approach would have been to multiply the potential damages by the probability of a plaintiff’s verdict to determine the expected value of the case.

The Mock Juries

To obtain better certainty about the strengths and weaknesses of the defendant’s case, ACE convened two mock juries. In one mock jury, four of eight mock jurors assigned 10% liability to Braswell and 90% to Bermea, three assigned 90% liability to Braswell and 10% to Bermea, and one assigned 60% liability to Braswell and 40% to Bermea. The other mock jury rendered a defense verdict assigning 100% of responsibility to Braswell.

What led to these conclusions? The mock jurors heard testimony that Brickman’s driver did not break any laws. Yet, even pro-defendant mock jurors felt that the truck was dangerously parked.

Additionally, several jurors believed the plaintiff’s theory that the truck must have stopped short or cut Braswell off so that he could not react in time. As a result, the mock juror report advised that “[i]t will be important to make clear to jurors that there is no evidence that Mr. Bermea cut off Mr. Braswell or stopped suddenly in front of him.”

Finally, and perhaps most critically, the mock jury did not hear evidence about Braswell’s daughter cutting herself, her attempted suicide, her hospitalization in the aftermath of her father’s death, or the fact that she left notes for her father near the accident site. Apparently, it was assumed that the judge would not permit such evidence to be admitted (even though he was pro-plaintiff).

A few days after the mock jury, a member of ACE’s internal team sent an email to Leibowitz and others stating that, “I feel for settlement purposes that this is more of a six figure case than a seven figure case.”

It is difficult to understand how anyone could reach such a conclusion. The mock juries had indicated that plaintiff’s “stopped short” theory was persuasive, and therefore the probability of a jury finding “no negligence” clearly went down. That would reduce the likelihood of a defense verdict below 70%, and increase the expected value of the case. Yet, no one appears to have questioned the assessment in the ACE email. The likely reason is that the feedback from the mock juries was not used to update the probabilities in the original decision tree analysis.

First Mediation

A mediation was held, but was unsuccessful because the offers were too far apart with plaintiff initially demanding $7.5 million (which unrealistically assumed a virtually 100% likelihood of plaintiff prevailing), and defendants initially offering only $100,000 (which unrealistically assumed a virtually 100% likelihood of defendant prevailing). We have previously discussed how bracketing and other impasse-breaking techniques can be deployed to to start reducing such a large gap, but apparently no such techniques were employed.

However, a different mediator approached by AGLIC later shared that plaintiff’s counsel was “a formidable opponent” and “has a huge presence in Houston, very well regarded personally and professionally.” The mediator also confirmed that the trial judge “tended to lean towards the plaintiff” on discretionary rulings.

A local Houston attorney subsequently expressed the view to AGLIC that “a Harris County jury would never decide that Braswell was 51% or more responsible because of the sympathy factor.”

AGLIC shared this information with ACE, but Leibowitz later testified that he had already incorporated these factors into his original analysis.

Second Mediation

A second mediation was also unsuccessful. The mediator advised AGLIC, however, that he thought the case was worth $2 million. Whereupon, AGLIC urged ACE to settle within ACE’s policy limits; ACE refused.

First Settlement Offer

Immediately after the second mediation, plaintiff’s counsel sent defense counsel a Stowers demand for the $2 million limit of the ACE policy. Based on the decision tree analysis set forth above, that was an extremely reasonable settlement offer — well within the expected value of the case ($1.8-$2.4 million) even before taking into account the additional information subsequently provided by the mock juries and discussions with the mediators and local Houston attorney.

It was thus not surprising that AGLIC’s representative demanded that ACE accept:

As you know, our mutual insured’s defense counsel evaluation of the Braswell claims includes a risk of a verdict in excess of the Chubb 2M primary limit. Defense counsel also evaluates the Braswell case for settlement up to your 2M limit. In other words, defense counsel does not opine that a defense verdict is a certainty or that an adverse verdict will not exceed Chubb’s primary limit. There is no such certainty given a variety of factors including, but not limited to: the well-regarded reputation and success of Mr. Mithoff; the expectation that Judge Sandill will favor plaintiffs, as he usually does, including on evidentiary issues; the $2.8M-$3.365M lost earning claim (deemed ‘certainly reasonable’ by defense counsel); respective consortium claims of the surviving spouse and two children; a conscious pain and suffering claim; sympathy factor for the surviving family; and the remote chance of a 51% fault allocation on the late Mr. Braswell by a Harris County jury. Therefore, Zurich agrees with defense counsel that a gross verdict could be as high as $8 million (if not more), which supports that the $2 million Stowers demand is reasonable.

ACE, however, refused to accept, and eventually countered with a “high/low offer” of $250,000/$2 million, meaning if the jury ruled against plaintiff, they would get no less than $250,000, while if the jury ruled against the defendants, they would pay no more than $2 million. Plaintiff declined.

The Trial Gets Underway

Meanwhile, the trial got underway. The judge promptly ruled against the defense on several key evidentiary issues. He:

- excluded evidence that the Brickman truck was parked legally (which had been a strong defense argument that had been compelling to the mock jury);

- permitted the introduction of evidence about the psychological state and self-destructive actions of Braswell’s daughter following her father’s death; and

- permitted testimony that was seemingly hearsay that the truck had stopped short.

Subsequently, the judge permitted a verdict form to list “soft” damages such as mental anguish separately for each of Braswell’s survivors. At closing argument, plaintiff’s counsel requested $10 million in general damages.

All of these rulings sharply increased the likelihood of a plaintiff verdict on liability, and increased the potential magnitude of the damages. Nevertheless, as the jury began deliberating, plaintiff’s counsel made a “high/low offer” to defense counsel of $1.9 million/$2 million.

After ACE rejected that proposal, plaintiff’s counsel renewed his offer to settle for the ACE policy limits of $2 million. ACE rejected this offer as well, and countered with a high/low of $650,000/$2 million, which plaintiff declined.

ACE’s representatives later testified that they continued to believe there was only a 30% probability of a plaintiff verdict — an obviously stale and outdated assessment in light of all the subsequent developments in the case (i.e., new information) and at trial (i.e., the judge’s evidentiary rulings in favor of plaintiff).

The Verdict

The jury returned a verdict of $39,960,000.00, apportioning 68% responsibility to the defendants and 32% to Braswell. The court entered judgment for $27,712,598.90 against the defendants after adjusting for comparative fault.

AGLIC ultimately took control of the settlement negotiations post-verdict after ACE tendered $2 million. AGLIC settled for $9,750,000, of which AGLIC paid $7,750,000. AGLIC then sued ACE for damages arising from ACE’s breach of its Stowers duty to accept plaintiff’s earlier reasonable settlement offers within the policy limits.

After a bench trial, the Court ruled in favor AGLIC, and awarded it a $7.2 million judgment against ACE. Clearly the right result.

Takeaway

The takeaway from this fascinating case is plain. Decision tree analysis is an incredibly valuable tool that, when properly used, can help a party accurately gauge the reasonableness of settlement offers, and decide whether to accept or reject them. But when used incorrectly (such as by failing to update the probabilities when new information becomes available), it can lead a party to make unreasonable choices.

*Source: Marc B. Victor, Litigation Risk Analysis & ADR (PDF)