Why Didn’t Amazon and New York City Mediate? A Pitch for Transactional Mediation

May 29, 2019The Merits of Med-Arb: If Mediation Fails to Resolve a Dispute, Should Parties Let the Mediator Arbitrate?

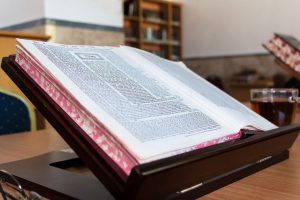

June 3, 2019Mediation Lessons From the Talmud: Four Lessons From the Disputes of the Academies of Hillel and Shammai

The Talmud is an ancient Jewish text (compiled around 500 C.E.) that is a primary source of Jewish law and philosophy. Its pages are filled with debates between various Sages concerning Jewish ritual (e.g., Sabbath, festivals) and civil law (e.g., contracts, torts, marriage, divorce), as well as numerous philosophical and theological issues. Given the centrality of dialectic to Talmudic discourse, it can serve as a useful source of dispute resolution principles for mediators.

The Talmud is an ancient Jewish text (compiled around 500 C.E.) that is a primary source of Jewish law and philosophy. Its pages are filled with debates between various Sages concerning Jewish ritual (e.g., Sabbath, festivals) and civil law (e.g., contracts, torts, marriage, divorce), as well as numerous philosophical and theological issues. Given the centrality of dialectic to Talmudic discourse, it can serve as a useful source of dispute resolution principles for mediators.

To illustrate, this post identifies four key dispute resolution principles emerging from the debates between two leading rabbinical academies that thrived in 1st Century B.C. Jerusalem and disputed literally hundreds of points of Jewish law: Beis Hillel (the House of Hillel the Elder) and Beis Shammai (the House of Shammai the Elder). We’ll first provide some historical context, and then highlight the relevant principles.

Historical Context

One of the Talmudic tractates, Ethics of the Fathers (or Pirkei Avos in Hebrew) (5:17), cites the debates of Beis Shammai and Beis Hillel as the paradigm of controversies that were for the sake of the truth. That is, neither side was motivated by self-aggrandizement or personal animosity, and neither side stubbornly stuck to its opinions. Instead, both schools were engaged in a search for the truth, and periodically relented when confronted with superior arguments or evidence supporting the opposing position (see, e.g., Tractates Eduyos 1:4, Pesachim 88b, and Gittin 41b).

The Talmud (Tractate Berachos 51b, Yevamos 14a) ultimately concludes that the law should follow the opinions of Beit Hillel because they constituted a majority. Elsewhere (Tractate Eruvin 13b), the Talmud adds that, while Beit Shammai’s opinions were also sound and well-reasoned, the law follows the opinions of Beis Hillel because they showed respect for Beis Shammai by teaching both their own opinions and Beit Shammai’s opinions (even going so far as to recite Beis Shammai’s opinions ahead of their own). This is similar to how American judicial opinions cite majority, concurring and dissenting opinions (and not just the majority opinion; albeit in American caselaw, the majority opinion always comes first).

Despite their ongoing disagreements, the two schools maintained cordial relations. In particular, while they held different views concerning certain laws pertaining to marriage and divorce, the families of the students of Beis Shammai and Beis Hillel still intermarried (see Tractate Yevamos 13b).

It is therefore surprising to read of an incident recorded in the Jerusalem Talmud (Shabbos 1:4) that, on its face, appears to indicate that Beis Shammai resorted to physical threats, and possibly even violence to impose their will on Beis Hillel in connection with the enactment of certain legislation:

These are the laws that were enacted in the upper chamber of the dwelling of Chananyah ben Chizkiah ben Garon when a large contingent of students from Beis Hillel and Beis Shammai went to visit him. On that occasion the students of Beis Shammai outnumbered those of Beis Hillel [and thus were able to pass certain enactments over Beis Hillel’s objections by a majority vote] . . . That day was a tragic one . . . Students from Beis Shammai positioned themselves below and made sure they retained their majority by threatening to slay any students from Beis Hillel who attempted to ascend to the upper chamber [to spoil Beit Shammai’s majority].

The commentaries dispute how literally to interpret the incident above. A leading German sage from the 1800’s, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, categorically rejects the implication that there were any physical threats, let alone violence or murder:

[I]t is clearly absurd to accept the notion that the Shammaites had used violence, in fact murder, to force a vote in their favor. For of what value would such a vote have been if it had been achieved by means of physical violence? . . . What good would have come from such terrorism? (Collected Writings, Vol. V, p. 87).

Rabbi Hirsch observes that the Babylonian Talmud (Tractate Shabbos 17a) records a similar incident involving the founders of the two schools, Hillel and Shammai (rather than their disciples), during which Hillel submitted to the authority of Shammai on particular issues. That incident is also described as tragic, and appears to arise out of the same visit to Chananyah’s dwelling that was recorded in the Jerusalem Talmud. But there is no mention of any physical violence.

Rabbi Hirsch also points out that immediately after the Jerusalem Talmud relates the purportedly violent acts of Beis Shammai, it indicates that the outcome of the incident was that eighteen decrees were enacted unanimously, another eighteen decrees were passed by Beis Shammai due to their majority, and yet another eighteen decrees were not passed due to a lack of consensus. If it were true that Beis Shammai enacted legislation using physical coercion, why weren’t they also successful in compelling passage of the eighteen decrees for which there was no consensus? Beis Shammai should have simply used the same physical threats to ram through those decrees as well. Moreover, eighteen decrees were passed unanimously, which suggests a degree of collaboration (not confrontation) between the two schools on that day.

For all these reasons, as well as the evidence of good will and cordial relations between the two schools (as noted above), Rabbi Hirsch concludes that the Talmud uses figurative language to convey that Beis Shammai acted assertively during that particular incident to compel Beis Hillel to bring certain important issues to a vote.

If, however, Rabbi Hirsch is correct that the incident should be interpreted in a positive light, why do the Babylonian Talmud and the Jerusalem Talmud both characterize the incident as tragic? A possible answer is that, as a matter of principle, the Talmud criticizes scholars whose legal disputes lead to personal animosity. For example, in Tractate Yevamos 62b, the Talmud records that a large number of students of the great sage Rabbi Akiva mysteriously perished within a short timeframe because, it is said, “they did not behave respectfully towards one another.” A leading Polish sage of the 20th century who wrote extensively on Jewish ethics, Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan (a/k/a the Chofetz Chaim), discusses the incident and explains that it is particularly shameful when prominent rabbinic scholars behave disrespectfully towards each other in public (see Kuntres Chovas HaShemirah, Introduction, paragraph 8 ).

Thus, it may be that while not becoming violent, the interactions between Beis Shammai and Beis Hillel during the relevant incident became heated, and degenerated into a level of disrespect that was deplorable given their prominent stature within the community. In other words, while the passage of numerous decrees through Beis Shammai’s well-intentioned assertiveness was a noteworthy accomplishment from the standpoint of legislation, the departure from the civility that had previously marked the debates between the two schools was tragic. Certainly a vital message for our times.

Mediation Principles

Regardless of what actually transpired during the incident recorded by the Talmud, the complex relationship between Beis Hillel and Beis Shammai conveys at least four vital principles of conflict resolution that can be applied in mediations.

First, we learn the value of validating the views of our adversaries. As noted, both Beis Hillel and Beis Shammai held well-reasoned opinions, but the law followed the opinions of Beis Hillel because they sought to understand and respect Beis Shammai’s positions. The message is that, during conflict, we should not just aggressively advance our own position, but as much as possible, step into the shoes of our opponents, and attempt to comprehend their viewpoint as well. As noted in a previous post on the role of empathy in mediation, particularly in disputes where there is a strong emotional component, it is up to the mediator to employ strategies that encourage parties to explore the perspective of the other side, and arrive at mutual understandings.

Second, disputants should not stubbornly stick to rigid positions, but instead remain sufficiently open-minded and flexible to adjust their positions based on the weight of the objective evidence and applicable law. To this end, a skillful mediator can help both sides evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of their respective positions.

Third, disputes should not become personal. As noted, despite persistent disputes over myriad subjects, the families of Beis Shammai and Beis Hillel still maintained cordial relations.

Fourth, in the context of any disagreement, despite the best intentions of the participants, there is always a risk that the dispute will degenerate into personal attacks. Indeed, even if the dispute between Beis Hillel and Beis Shammai did not actually become physical or violent (as Rabbi Hirsch maintains), the plain text of the Jerusalem Talmud may still deliberately suggest otherwise precisely to teach that even violence becomes possible when disputes become too heated. As such, both sides to a dispute should remain alert to subtle shifts in tone or rhetoric indicating that the debate is transitioning from problem solving to ad hominem, and seek to revert to civility.

A mediator obviously plays a critical role when it comes to maintaining civility during joint sessions so that each side can speak without interruption and feel it has been adequately heard. Among other things, the mediator can model civility through his or her own conduct such as tone of voice. At the same time, the mediator also needs to remain alert to any changes in the mood, and intervene if either party breaches the ground rules of civility.